Could the CMA’s markets regime do more to promote innovative services?

In 2017, the UK’s Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) introduced a number of changes to streamline the way it runs market investigations – a unique feature of the UK competition regime and one of the most powerful tools in the CMA’s regulatory arsenal for unlocking barriers to innovation and transforming the way markets work for consumers. Now, as the CMA’s first probe under the new regime draws to a close – and with its new chairman signalling further changes on the horizon – we assess whether concerns about the new approach have been borne out in practice and consider the implications for forthcoming investigations.

The changes that the CMA made to its market investigation process were far-reaching. They included:

- sharing with stakeholders more of the thinking behind the probe in its early stages and in the initial market study phase before the full investigation gets underway;

- assessing potential remedies to improve the market at an earlier stage in the investigation; and

- reducing the number of formal publication and consultation stages.

The CMA’s motives were understandable. Two high-profile investigations into the energy and retail banking sectors, which both peaked in 2016, each took two years to complete (even before one considers the time spent on implementing the CMA’s remedies), with several hundred submissions by industry stakeholders, several thousand pages of CMA publications and dozens of hearings. However, the CMA’s consultations also revealed concerns about whether a more streamlined process would compromise the regulator’s ability to carry out a fair and robust investigation.

Nearly two years on, the CMA is putting the finishing touches to its first investigation under the new streamlined procedures. So how have the reforms played out practice?

What did the market investigations regime ever do for us?

In considering the impact of the reforms, it is worth recalling why the CMA’s markets regime is so important. Unlike other mechanisms at its disposal – investigations into cartels and abusive behaviour by dominant firms and the like – the CMA can use its probes to make a holistic assessment of how markets function and to push through changes even when there has been no infringement of competition law. This means that investigations have a special role to play in unlocking innovative business practices that would be unachievable without central coordination.

Thinking of regulators as champions of innovation may seem unorthodox. After all, decentralised markets are often held up as powerhouses of invention that work precisely because they allow consumers, rather than policymakers or regulators, to decide whom to back: firms that have clever ideas and find good ways of bringing them to market will flourish; those that do not will wither on the vine. According to this line of thinking, the main role of regulators is to promote an environment in which competition can function effectively – and in which good ideas are consequently rewarded – rather than picking winners directly.

But sometimes innovation needs a firmer guiding hand. This is particularly the case for good ideas that require interoperability between firms, which therefore have to coordinate their behaviour accordingly. This is difficult to achieve in a decentralised competitive market environment.

Open Banking is a powerful case in point. For a number of years industry stakeholders and consumer groups in the retail banking sector had been discussing how to allow consumers and small businesses to share their bank account data with third parties other than their existing lender. The idea was to make it easier for other banks, price comparison websites and fintech companies to develop and offer additional or more personalised services. Customers would benefit from new services, especially those tailored to their specific needs, and would learn more about the benefits of shopping around. As a result, Open Banking would spur increased competition and deliver better outcomes for consumers.

The problem was that finding ways of sharing sensitive individual customer account data in a standardised way would be extremely difficult – if not impossible – without central coordination and regulatory support. In the UK, the CMA was able to use its market investigation regime as a vehicle for exactly this purpose, introducing a set of common standards for banks to share data with third party service providers. As a result, the UK has been first out of the starting blocks. In 2018 it became the first country in Europe – and indeed the world – to make Open Banking a reality.

A remedied remedies process?

Retail banking was, however, the final investigation that the CMA conducted under its old process. An important question, therefore, was whether the new, more streamlined procedures would allow the CMA to use its market investigation powers in the same way.

The CMA’s first (and at the time of writing only) investigation based on the new methodology focused on the investment consulting sector. Investment consultants advise pension trustees, who oversee companies’ defined benefit pension schemes, on how to ensure they can meet the financial commitments to their members through appropriate risk management and investment of their funds. The industry was referred to the CMA by the UK Financial Conduct Authority (FCA), which had identified a number of features of the sector that could potentially impair competition – namely a weak demand side, with trustees relying heavily on consultants but limited in their ability to assess the quality of their advice or compare the services on offer; relatively high levels of market concentration in investment consulting, and possible barriers to expansion.

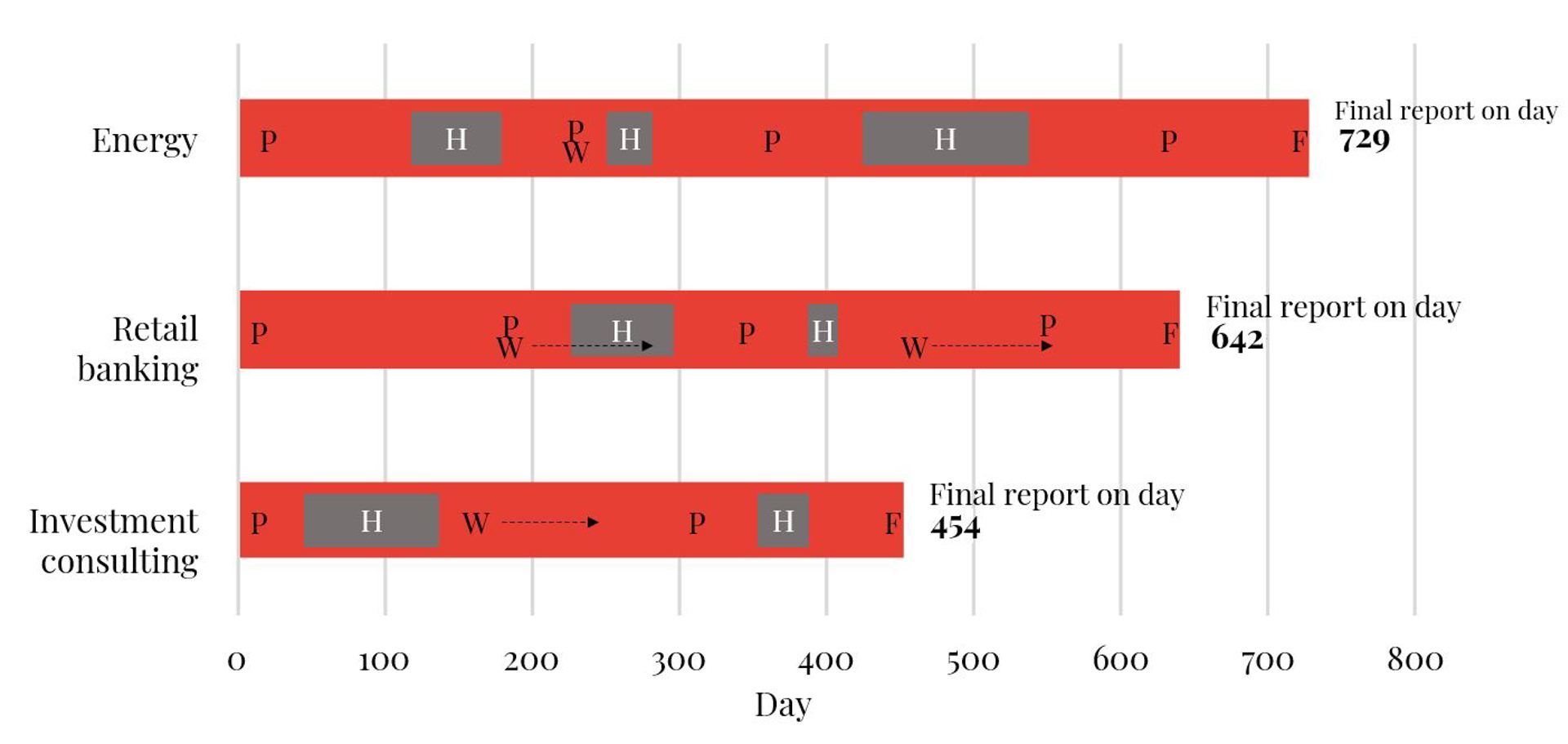

On one level, the new regime was a success – the CMA stuck to the new process and completed its investigation in 15 months, compared to 24 months for the energy probe and 21 months for the retail banking investigation. As the chart below illustrates, the new process was not only simpler but also brought forward the first round of hearings much closer to the start of the process. This early engagement quite quickly enabled the CMA to shine a clearer light on the structure of the supply side of the market than had been possible in the initial market study phase – establishing, for example, that levels of market concentration were in fact relatively low.

Shorter and simpler? The timetables of the CMA’s three most recently completed market investigations:

Source: Frontier Economics

Notes: H = main hearing periods; W = main CMA working paper publication periods; P = other key interim CMA publications; F = final report

But questions remain whether the new streamlined procedure gave the CMA sufficient time to get to grips with the real challenges confronting the sector – and whether its resulting remedies package was as effective as it could have been in finding innovative ways to help the industry address these challenges.

A scan of the remedies set out by the CMA in its final report would suggest that almost all the problems facing the industry relate to a relatively new service called fiduciary management (FM). FM, which has come to prominence in recent years, involves a greater degree of delegation than traditional investment consulting. Rather than solely giving advice, FM providers also make and implement investment decisions based on the pension scheme's investment strategy. From an early stage of the investigation, the CMA indicated that it had more concerns about FM services than advisory-only services. It suggested, for example, that firms offering both may have an incumbency advantage in selling FM services to their existing advisory customer base, and that trustees often selected their FM provider without shopping around or running a competitive tender process.

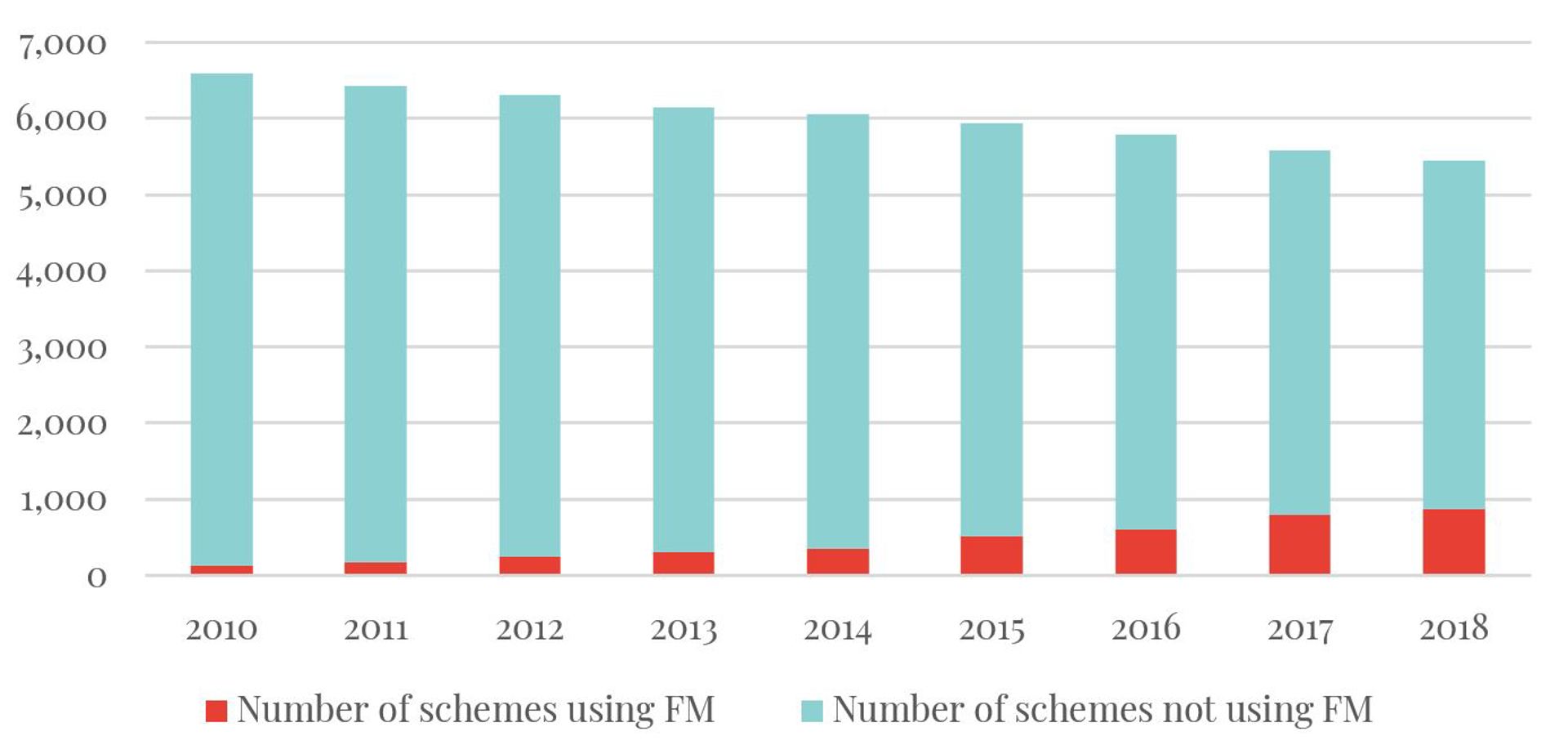

In practice, a number of the measures that the CMA introduced to promote competition in FM – such as steps to encourage competitive tendering and to help standardise the reporting of fees and past performance – seemed sensible. However, the CMA failed to consider some of the tests facing the industry. In particular, the penetration of FM services in the UK remains surprisingly low compared not only to advisory-only services but also to FM penetration rates in some other economies such as the Netherlands. According to estimates by KPMG, only 15% of UK DB schemes engaged with a fiduciary manager in 2018.

Still a long way to go … the evolution of schemes using/not using FM since 2010:

Source: Frontier Economics analysis of data from KPMG and Pension Protection Fund.

This would not matter if FM were a niche product of value only to a small subset of trustees. But FM is a market-led innovation that is designed to alleviate some of the core difficulties facing pension schemes and their trustees. The UK pensions industry is highly fragmented with nearly 6,000 defined benefit schemes. The effects of this fragmentation are twofold: first, it reduces the bargaining power of individual trustees (for example in negotiating fees with asset managers); and second, it means that resources and expertise are thinly spread across the industry, such that trustees often find it difficult to make properly informed decisions about the investment opportunities available or the quality of the advice they are receiving.

FM services are designed to tackle the problems posed by fragmentation in a number of ways:

- By delegating fund investment decisions and execution to FM providers, trustees have more time to focus on overarching strategy, asset allocation and critical risk management questions.

- Delegation lets trustees tap into expertise that they do not possess in-house in areas such as sophisticated investment and risk management.

- By implementing the investment strategies of multiple pension funds simultaneously, FM providers have more bargaining power with fund managers, with cost savings typically passed on to trustees.

- Trustees can directly appraise the performance of FM providers, whereas it is harder to assess the record of advice-only consultants because trustees do not always follow their recommendations.

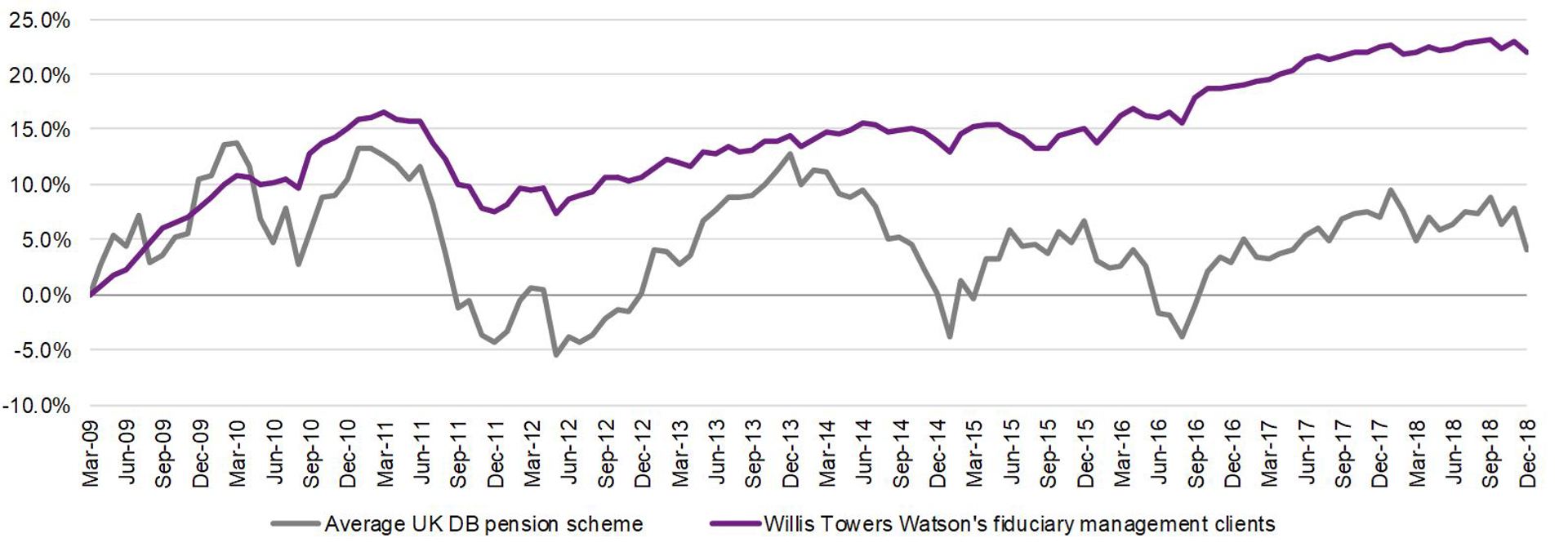

And FM appears to bring results. As the grey line in the chart below shows, there has been no material improvement in average defined benefit pension scheme funding levels in the UK over the last decade; instead, funding levels have been characterised by a high level of volatility, with periods of growth offset by periods of decline. By contrast, FM has a strong record both in improving average funding levels and reducing volatility – as illustrated by the purple line, which shows the performance of FM clients of one such provider, Willis Towers Watson.

Changes in pension scheme funding levels over time:

Source: Willis Towers Watson

In light of these findings, it is surprising that the take-up of FM services has not been more widespread. There are several possible explanations for this:

- Those pension fund trustees with potentially most to gain from FM are also those with the least time or experience to explore alternatives to their existing advisory services.

- Some investment consulting firms still operate advisory-only models and so have no incentive to offer FM as an alternative. Trustees may thus have little awareness of FM options and benefits.

- Some trustees feel responsible for making decisions and may regard delegation as inconsistent with this duty, while others enjoy being directly involved in making investment decisions. And trustees who are familiar only with the advisory model may harbour a fear of the unknown.

- KPMG’s 2018 update revealed the gradual growth in FM penetration had stalled, perhaps in part due to uncertainty created by the CMA’s investigation.

A number of market participants raised these issues with the CMA at more than one stage in its investigation. However, the CMA never fully engaged with them. Nor did it clearly explain why it did not consider these issues to be important enough to warrant further analysis. The contrast with the banking investigation – where the CMA got to grips with the core challenges facing the sector and coordinated an innovative remedy – is striking.

This prompts the question of whether the current market investigation process is tying the CMA’s hands and leaving it underpowered to promote and champion innovation. The CMA’s desire to accelerate the timetable for investigations where possible is understandable. But it would be a shame if this came at the expense of its ability to dig into the challenges facing the industries under its microscope – and thereby unearth and unlock innovations designed to overcome them. The CMA may be wary of being seen to pick the winners when it comes to promoting specific innovations in a competitive market. However, if the CMA’s package of remedies ends up placing more obligations on some services models than others – as was the case in the investment consulting investigation – then it may end up picking “regulatory winners” in any event.

Looking ahead

The CMA’s thinking on market studies and investigations looks set to evolve further. In a recent letter to the government, the new chairman of the CMA, Andrew Tyrie, argued that there were “significant defects” in the current markets regime and set out some high-level proposals for reform. Some of these – such as a proposal to align the scope of market studies and investigations more closely with a view to creating a more joined-up process – look sensible in principle. But another proposal – to allow the CMA to impose “legally enforceable requirements on firms on an interim basis” pending the completion of its market investigation – is likely to prove controversial. Tyrie justified his proposition by citing “growing demands for swifter intervention in the face of consumer harm”. But care will be needed to ensure that any such measures are founded in evidence and that they do not disproportionately damage competition – and ultimately consumer welfare – in the event that the remedies are ultimately found to be unwarranted. Perhaps most importantly, the CMA should ensure that the steps it has in mind do not lead to a focus on quick fix solutions. These might mitigate some of the symptoms of the competition problems the regulator identifies, but they would risk stifling the CMA’s ability to champion the real innovations needed to help resolve the underlying causes of these problems.

Note: Frontier Economics advised SSE, Lloyds Banking Group and Willis Towers Watson on the CMA’s investigations into energy, retail banking and investment consulting respectively. The views expressed in this bulletin are solely our own.