USING ECONOMICS TO RESOLVE MULTINATIONAL TAX DISPUTES

The tax arrangements of multinationals have attracted increasing public attention over the last 20 years. But despite legislative changes and increasing political pressure, authorities still struggle to successfully challenge the pricing of intra-group transactions. While there is plenty of published guidance, and lots of opinion, much transfer pricing still operates on rules of thumb and opaque negotiation. Only a few disputes ever reach court, but ten years ago Frontier used economic analysis to help HMRC win a landmark international tax case. This article explores the ways in which the competition economist’s toolkit can be used to resolve such questions, which are of increasing importance and frequency in globalised markets.

Globalisation and digitisation are two very powerful trends that continue to shape the world economy. As shopping habits change, and tech companies disrupt traditional markets, these trends are having a significant impact on a range of policy issues, including competition regulation and data protection. They are also at the heart of economic, business and social changes, such as the decline in high street retailing. For tax authorities, the combination of these trends provides a threat to established tax bases, and traditional approaches are struggling to deal with business models that cannot be fitted neatly within local or even national boundaries.

This has intensified the pressures faced by tax authorities across the world. There is plenty of published guidance and a long tax rulebook. And there is lots of opinion available from tax professionals, authorities and politicians on what the outcome should be, and (less often) how to reach it. But it remains the case that only a handful of significant transfer pricing cases have ever reached court. Frontier provided expert advice in one such landmark case ten years ago.

Questions of transfer pricing, like questions of competition policy, ultimately come down to working out where and how value is generated. So our “novel” approach was to use the toolkit that economists (and lawyers) use as standard in competition policy, and which underpins the OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines (see Box 1).

The DSG case showed that the UK authorities were comfortable departing from traditional transfer pricing methods when necessary, and that an economic analysis of market outcomes was supported for use in tax cases. Where comparables were hard to find, or the products and services being analysed were genuinely unique, this suggested economic analysis (based on competition economics frameworks) would perform a highly valuable role.

More recently, the European competition authority has also applied competition law in a number of state aid cases involving transfer pricing issues. Competition economics has developed a robust and well-established approach for doing this, much of which is transferable to other disputes about value. Accordingly, tax authorities outgunned by multinationals, and businesses locked into long-running disputes, can all benefit from greater knowledge-sharing between tax and competition economics, which may provide a new way through long-running cases.

And yet, since DSG, there has only been a trickle of further transfer pricing cases using an economic approach. Much of the transfer pricing world today still operates using untested rules of thumb and opaque negotiated outcomes. As with DSG, when the economic approach has been tested in court, it has passed, but in our experience tax authorities and practitioners have generally been slow to recognise the power of economics as a toolkit to address transfer pricing questions.

BOX 1

LANDMARK FOR THE TAXMAN

Dixons Stores Group (“DSG”) was the biggest retailer of electrical goods in the UK, and sold extended warranties with many appliances. The warranties were re-insured with a captive insurance business in a low-tax jurisdiction. HMRC challenged the pricing of this insurance, arguing that the premiums paid to the captive insurer were “too high”, and the case came to judgment in 2009.

DSG’s case focused on the operation of the insurance business, with little discussion of the retail activities. A small number of comparators for specialised re-insurance of warranties were identified, with an emphasis in the analysis placed on risk and reward. DSG ultimately argued there were few commercial alternatives to the arrangements.

In Frontier’s expert witness testimony, we assessed the arrangements from a competition economics perspective, consistent with the OECD Guidelines. Our analysis identified that:

— There was a market for electrical warranties, with the majority sold by retailers of electrical goods (DSG being the largest player). Warranties generated above-normal levels of profit.

— Many insurers could provide the re-insurance that was being provided by the captive insurer. Insurance markets were competitive, and competitive insurance services were easy to find. — The high level of insurer profit observed was ultimately generated through the retail “point-of-sale” advantage enjoyed by DSG.

— DSG’s position in the market was unique and it could contract with many different insurers; a position which was not reflected in the comparators it put forward.

— There was little genuine risk being faced by the captive insurer. The contract structure meant the rewards were flowing to the “wrong” party, as revealed by an assessment of which party was actually generating the value.

In the court’s judgment, the DSG comparators were rejected, and no alternatives identified. The economic analysis presented was deemed to support a profit-split analysis, the conclusions of which were that the captive insurance business should earn no more than a normal rate of return. This had the effect of moving a significant amount of profit (and tax) back into the UK.

TAX AND COMPETITION: BROTHERS-IN-LAW?

The starting point for transfer pricing within multinationals is the “arm’s length principle” set out in the OECD’s model tax convention (the application of which is discussed in the OECD’s Transfer Pricing Guidelines). In essence, this says that transactions between two companies that are part of the same group, but located in different tax jurisdictions, should be priced as if they had been made between independent companies.

By contrast, when competition authorities investigate markets or mergers, their reference point is the expected outcomes of a competitive market. There are variations in competition law between jurisdictions, but across Europe, the US and much of the rest of the world, the legislation focuses on two prohibitions: of agreements or practices that restrict or distort competition; and of behaviour that exploits market power and artificially limits competition.

However, from an economist’s perspective there is a significant overlap between these two. The pricing of a transaction between two independent entities is also a market outcome, and will be shaped by the parties and the competitive environment in which they operate. The only difference is that while competition policy practitioners take hypothetical competitive market outcomes as a reference point for understanding the actual market outcomes they observe, tax practitioners seek to establish what the actual market outcomes would be for two hypothetical independent businesses (recognising that they may or may not operate in competitive markets).

Determining whether prices, and by implication the resulting profits, are acceptable is therefore both the fundamental task of transfer pricing for tax purposes, and the focus of many competition investigations. But practitioners in each discipline have traditionally used different tools.

In the tax world, most transfer pricing analysis starts by considering the suitability of the OECD’s “traditional methods”. These are typically interpreted as a hierarchy of benchmarks: starting from a “comparable uncontrolled price” for the same transactions taking place at arm’s length, and then moving to a series of comparisons of different forms of profit margin.

Where no identical transaction can be identified, consideration can be given to the ways in which other comparable prices or margins might be adjusted to form suitable benchmarks (although much transfer pricing analysis stops at identifying the set of comparables, without seriously considering whether adjustments are necessary). This focus on comparable prices and benchmarking simple margins follows naturally from the objective of testing prices against what is observed in the open market. Clearly, where straightforward price comparisons are available, it makes sense to use them. But the guidelines then suggest that other forms of “transactional profit” analysis, including net margin ratios and profit-split analysis, might be useful if these traditional methods cannot be applied. (The OECD’s Transfer Pricing Guidelines provide many cautions and caveats on the use of different measures, the need for adjustments to be made and the availability of data needed to make those adjustments.)

In the competition world, practitioners tend to reach more quickly for the tools of profit analysis because they have the slightly different objective of testing against competitive outcomes. If you suspect that competition is not working well in the market, comparing the prices of different suppliers may not be informative (because more than one supplier may be benefiting from the lack of competition). Focusing directly on profits may get you to the answer more quickly. Economic profit analysis enables practitioners to use standard corporate finance techniques to test rates of return on investment against the cost of capital for a business, as the economics dictates that in a competitive market, profits cannot be sustained above this level.

BOX 2

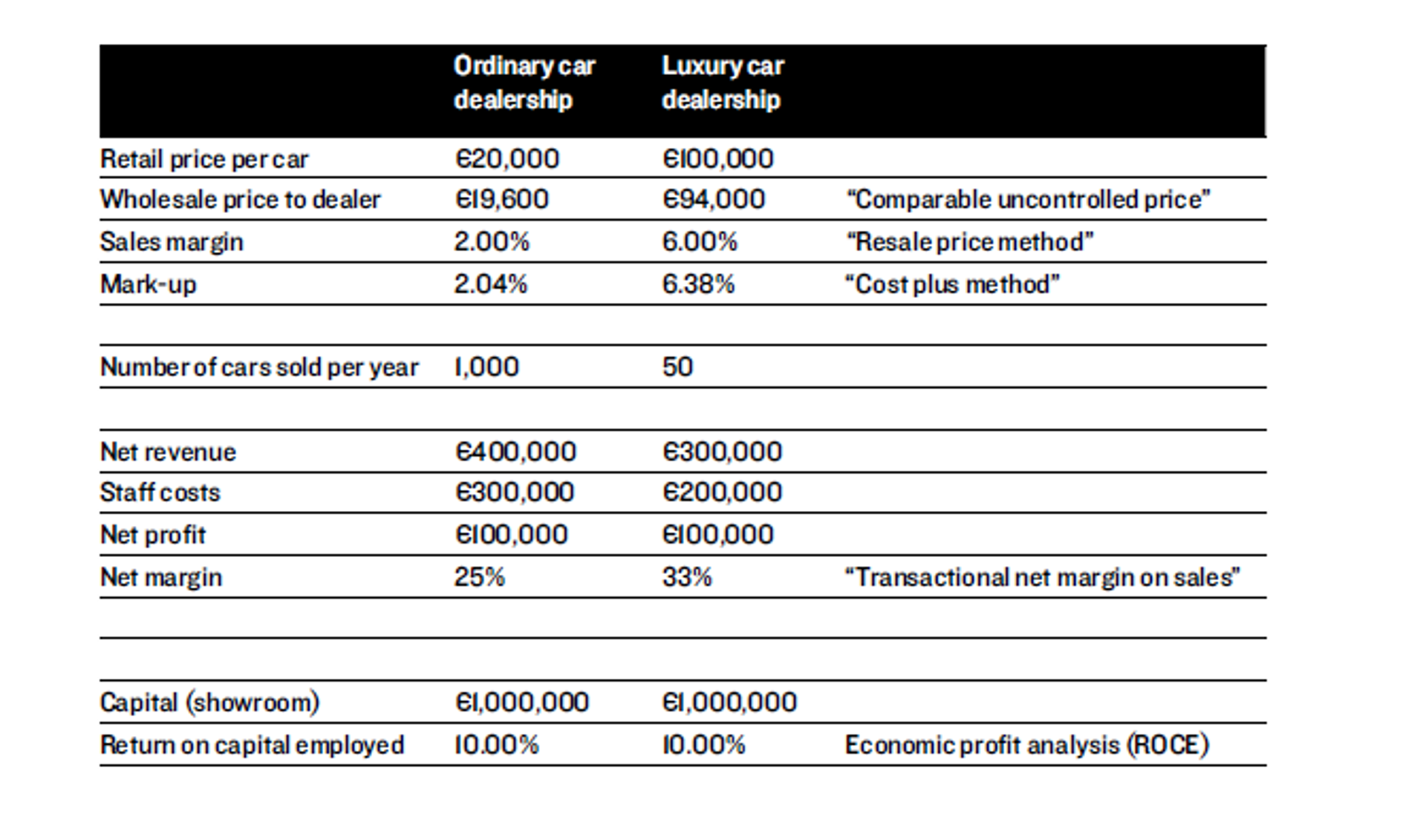

ROLLS-ROCE?

This simplified example shows how economic profit analysis can help comparisons between different businesses. Two car dealerships sell different cars; the first sells family hatchbacks, the second sells luxury cars. Both own their own premises, hire their own staff and buy the cars from the manufacturer. One is essentially “high volume, low margin” and the other vice versa. As a result, many of the simple price and margin comparisons do not stack up. From an economics perspective the one thing that we would expect to be able to directly compare is the profitability. If both dealers operate in competitive markets (against other dealers selling the same cars), we would expect them to generate similar rates of return on capital employed.

CAPITAL BENCHMARKS

Because most large businesses will have their own estimates of their cost of capital (for internal investment appraisal purposes), at least one simple benchmark is usually available. Further, well-established techniques for creating company, sector and country-specific estimates of the cost of capital have been widely adopted by competition authorities and sector regulators around the world. Use of the capital asset pricing model in competition investigations has been endorsed repeatedly in legal precedent, not least because it would form the basis of much commercial investment appraisal.

Of course, economic profit analysis and investment appraisal techniques are familiar to most tax practitioners and are themselves recognised in the OECD Guidelines’ acceptance of “transactional profit methods”. What is different is the preference generally given to different methods and how the benefits of them are perceived.

To a competition practitioner, the ability to test profits (and hence prices) for different businesses against company and industry benchmark rates of return can simplify many cases where price comparisons may not make sense. For transfer pricing, the traditional emphasis on price or margin comparisons can sometimes result in convoluted efforts to adjust the prices of different transactions to make them comparable. Economic profit analysis can, as Box 2 shows, provide a complementary approach.

Things are straightforward in both the tax world and the competition world when looking at how competitive businesses carry out commonplace transactions. Market prices can be readily observed, profits tend towards normal levels and analysis is straightforward. In both worlds, things become more complex when we introduce assets or capabilities that are not run-of-the-mill. In the Transfer Pricing Guidelines, particular attention is given to the existence of unique assets (tangible or intangible) and to “activities of economic significance”. In the competition world, the focus is on potential “sources of market power”, “barriers to entry” and sources of “competitive advantage”.

The underlying economics is the same; it is about identifying scarce, valuable assets and capabilities that are difficult for others to replicate. Or in other words, the fundamental economic concept that underpins both a tax and a competition analysis is identifying where and how value is created.

In competition economics, over time a body of case law has been established that has delivered a commonly agreed framework and empirical approach to analysis. There is now a well-established framework for defining markets and assessing market power within them, for identifying barriers to entry, and for analysing potential sources of competitive advantage, as illustrated by the EC judgement on Google Search, from which extracts are given in Box 3. These concepts are central to almost every merger investigation and market inquiry made by competition authorities across Europe, North America and beyond.

The OECD’s Transfer Pricing Guidelines recognise these concepts, but provide limited guidance on how to analyse them. In the absence of an equivalent body of substantial case law to draw on, this can create a vacuum for speculative claims to the relative importance of different activities to be made. Not only does this create uncertainty for tax authorities and taxpayers alike when designing transfer pricing arrangements, it also reduces the ability of both sides to run efficient negotiation processes where there is a difference of views.

However, all is not lost. Rather than wait for decades of case law to be established in the tax world, it should be possible to shortcut the accumulation of precedent by using many of the principles and techniques established in the existing competition economics case law.

The standard competition framework for market definition focuses on the degree to which alternative sources of supply or demand are substitutable i.e. could somebody supply the same product or service, or would a customer be willing to switch to an alternative. The analysis of entry barriers addresses the same issues but asks how easy it would be for a third party to enter or expand into the business in question. From a transfer pricing perspective this is in essence the test of the “economic significance” of an activity. If an activity is easily replicated (i.e. there are alternative sources of supply readily available, or other providers could rapidly enter and supply the same service), then its ability to generate anything more than a normal rate of return is limited.

The history of applying these concepts in competition investigations means that there is now a substantial body of past studies, cases and judgements, in a wide range of industry sectors, to draw from. So as well as legal precedent on methodology, there is a considerable amount of industry evidence, analysis and testimony that tax practitioners could use. In industries from banking to pharmaceuticals, automotive to mobile telephony, insurance to mining, brewing to luxury goods, there have been mergers inquiries and studies that can provide valuable insight.

BOX 3

MARKET DEFINITION? GOOGLE IT!

These heavily footnoted paragraphs from the 2017 EC antitrust decision on Google Search show how the standard approach to analysing markets has been tested and become well established through precedent.

145. For the purposes of investigating the possible dominant position of an undertaking on a given product market, the possibilities of competition must be judged in the context of the market comprising the totality of the products or services which, with respect to their characteristics, are particularly suitable for satisfying constant needs and are only to a limited extent interchangeable with other products or services. 66

146. Moreover, since the determination of the relevant market is useful in assessing whether the undertaking concerned is in a position to prevent effective competition from being maintained and to behave to an appreciable extent independently of its competitors and its customers, an examination to that end cannot be limited solely to the objective characteristics of the relevant services, but the competitive conditions and the structure of supply and demand on the market must also be taken into consideration. 67

147. A relevant product market comprises all those products and/or services which are regarded as interchangeable or substitutable by the consumer, by reason of the products’ characteristics, their prices and their intended use. 68

148. The relevant geographic market comprises the area in which the undertakings concerned are involved in the supply and demand of products or services, in which the conditions of competition are sufficiently homogeneous and which can be distinguished from neighbouring areas because the conditions of competition are appreciably different in those areas. 69

66 Case T-229/94, Deutsche Bahn v Commission, EU:T:1997:155, paragraph 54; Case T-219/99, British Airways v Commission, EU:T:2003:343, paragraph 91; Case T-321/05, AstraZeneca v Commission, EU:T:2010:266, paragraph 31.

67 Case 322/81, NV Nederlandsche Banden Industrie Michelin v Commission, EU:C:1983:313, paragraph 37; Case T-556/08, Slovenská pošta v Commission, EU:T:2015:189, paragraph 112. See also Commission Notice on the definition of relevant market for the purposes of Community competition law (“Commission on market definition”), OJ C 372, 9.12.1997, p. 5.

68 Commission Notice on market definition, paragraph 7.

69 Source: European Commission Decision (27.6.2017) relating to proceedings under Article 102 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union and Article 54 of the Agreement on the European Economic Area (AT.39740 – Google Search (Shopping)).

SEEING THE "WOULD" FOR THE TREES

One of the thornier issues in transfer pricing is the “would” question: the circumstances under which a tax authority must accept that a particular transaction “would” actually take place between independent parties, and the circumstances where this may be disregarded. This issue is more formally described in the OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines as “recognition of the appropriately delineated transaction” and is summarised as follows:

…The key question in the analysis is whether the actual transaction possesses the commercial rationality of arrangements that would be agreed between independent parties under comparable economic circumstances, not whether the same transaction can be observed between independent parties.

While looking for examples of similar transactions can provide evidence that certain types of commercial arrangements do exist, providing evidence that a given deal would never happen can be a much greater challenge for authorities. Proving this requires some logical basis on which to demonstrate that a deal would not make commercial sense. Again, there are parallels in competition economics that can help.

The question of whether certain types of commercial behaviour would make sense is also a standard question faced by competition authorities in a range of circumstances. When assessing mergers, the US and UK authorities consider the question: “Would the merger result in a substantial lessening of competition in the market?” The EU considers a similar one: “Would the merger significantly impede effective competition?” Answering these requires a careful assessment of how commercial behaviour would change as a result of the merger. The standard framework for competition assessments is to consider whether the merger transaction materially changes the ability of the combined firm to behave anti-competitively, and the incentives for such behaviour.

To perform such an analysis, competition practitioners would typically start by considering theories of harm: identifying the pattern of commercial behaviour that could pose a problem. Then they would test whether each pattern of behaviour would be more or less attractive to the merged company than the alternatives available to it. In other words, would the behaviours that harm competition be commercially rational and would the business be able to act in this way?

Take, as one much-discussed example, the Tesco-Booker merger in 2017. Surely the combination of two major players in the UK food sector would be harmful to competition, and the post-merger prices and services offered to corner shops would get worse? The detailed assessment by the UK’s Competition and Markets Authority took careful account of the economics of grocery wholesale and retail, the position of the companies in the relevant markets, and critically the commercial incentives on them as individual businesses and as a merged entity. It concluded that many of the worries were unfounded as it would simply not make sense for the business to worsen its offer to corner shops when so many other choices were available to them.

Similar questions and analysis are undertaken when considering allegations of predatory pricing (undercutting rivals to force them out of the market). In these cases it is again standard practice for competition authorities to consider the commercial rationality of such behaviour in terms of the long-term expected profitability of the business in question. If undercutting rivals means incurring losses, then competition practitioners would then consider whether the business could expect to recoup the value of losses in the future. If not, a finding against them is unlikely. Again the tools of economic profitability analysis and investment appraisal are often useful in this context.

CONVERTS TO THE CASE

Fortunately, we are not alone in our view that the competition economics framework is relevant to international tax issues. The most recent example of this approach gaining traction is the series of state aid cases: in the last three years, the European Commission has published its findings on a series of competition investigations into state aid issues relating to large multinationals.

While these investigations have been carried out by the EC’s competition directorate, they have scrutinised the transfer pricing arrangements of a number of high-profile multinational businesses including Amazon (see Box 4), Apple, Fiat, Ikea, McDonald’s and Starbucks. The resulting decisions overturned agreements put in place by local tax authorities and could require the businesses to pay back substantial sums to the member states. A number of these cases are now being appealed through the European Courts.

In connecting the frameworks of competition law with the OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines, the EC highlights one of the key areas of overlap between them. For a state aid investigation, one of the key questions is whether a business enjoys a “selective advantage” as a result of some state intervention. To identify a selective advantage in the context of transfer pricing arrangements the Commission focused explicitly on market outcomes as its interpretation of the OECD “arm’s length” principle.

This terminology has been used extensively by the Commission, for example in its decision on Apple in July 2017:

…Consequently, to ensure that a profit allocation method endorsed by a tax ruling does not selectively advantage a non-resident company operating through a branch in Ireland, that method must ensure that the branch’s taxable profit…is determined in a manner that reliably approximates a market-based outcome in line with the arm’s length principle.

These cases have attracted a lot of attention among both competition and tax practitioners. To the EC, control of state aid is a key plank of European competition policy and it is natural to use the tools of competition analysis to investigate it. So it is perhaps unsurprising that some of the decisions have focused on assessments of the degree to which the activities and capabilities of the different parties might be expected to generate anything other than a routine return, applying economic profit analysis to then determine the appropriate share of value. In some cases this has led the EC to reject simple comparators, and to undertake new economic profit analysis based on very careful scrutiny of the extent to which a business’s activities really are “routine”.

BOX 4

AN AMAZON PRIMER

The Amazon case focused on two Luxembourg-based businesses which sit at the top of Amazon’s European organisational structure. LuxSCS is a holding company designed to hold all of the intellectual property required for Amazon to operate in Europe. It had no physical presence or staff and was not deemed as separate to its US partners for tax purposes, and thus was not liable for corporation tax in Luxembourg. LuxOpCo operated as headquarters of the Amazon group in Europe and the principal operator of the European online retail and service businesses. It used the IP held by LuxSCS under licence.

The transfer pricing agreement in place was based on analysis which suggested that LuxOpCo should receive a return to reflect “routine functions in its role as the European operating company”. Based on comparators this was assessed to be in the range of 4–6% of operating costs, with the caveat that if actual operating profits were below this figure it should receive the lower amount. Any excess profits above this “routine” return flowed to LuxSCS, as holder of the “valuable intangibles”, and were not subject to local tax.

The EC’s own analysis of the economics of the two businesses concluded that LuxOpCo’s role was far from routine. While LuxSCS was the legal owner of the intangibles, it had granted:

…an exclusive and irrevocable licence to LuxOpCo for the economic exploitation of those intangibles for their entire lifetime…

In short, it decided that:

…LuxSCS does not perform any unique and valuable functions in relation to the Intangibles for which it merely holds the legal title under the Buy-In Agreement and the CSA…Instead, it is LuxOpCo that performs unique and valuable functions in relation to the Intangibles, that uses all assets associated with those functions, and that assumes substantially all the risks associated therewith.

The Commission essentially turned the transfer pricing arrangements on their head, deciding that it was more appropriate for LuxSCS to receive a “routine” mark-up on its activities administering legal ownership of the IP, while residual profits should remain with LuxOpCo and be taxed accordingly.

WHERE NEXT?

Ten years on from the DSG case, we remain convinced that the tools of competition analysis can provide valuable insights for transfer pricing purposes. It is reassuring to know that the European authorities feel the same way. Unpicking the pricing and profitability of any business is difficult, more so when looking at complex multinational structures that hold unique assets and prominent market positions.

The OECD continues to look for ways to develop the transfer pricing framework and recently invited public input on tackling the tax challenges of digitalisation. Sharing knowledge between the two disciplines of competition economics and tax can only help to enhance the state of the art, and may provide a new way through long-running cases. Equally, if tax authorities were to adopt the antitrust authority model by building up case law precedent in a predictable way, that would benefit all parties in the long run.