Forecasting the future can be challenging at the best of times, but as the world heads into 2023 the outlook seems particularly uncertain.

Against the backdrop of a lingering pandemic, a European war, rocketing inflation, the fallout from Brexit and growing tensions between the world’s two economic superpowers, making just about any prediction in the field of economics or policy can feel like a fool’s game. Nonetheless, Frontier’s competition team have put their cards on the table and predicted four themes that will feature prominently in competition law debates this year in Europe and elsewhere. These are:

- growing pressure on competition regulators to intervene in the cost-of-living crisis;

- the ongoing ‘digital revolution’ in antitrust, as new competition regimes for digital markets come into contact with reality;

- the transformation of the competition litigation landscape in Europe, with the rise of collective claims; and

- louder – and sharper – debates around subsidy control.

1. A more targeted response to the cost-of-living crisis?

With consumers across Europe facing an unparalleled squeeze on living standards, lawmakers and regulators alike will come under intense pressure to show they are doing whatever they can to help bring inflation under control while mitigating the worst effects of what looks set to be a drawn-out recession. Competition authorities will be no exception.

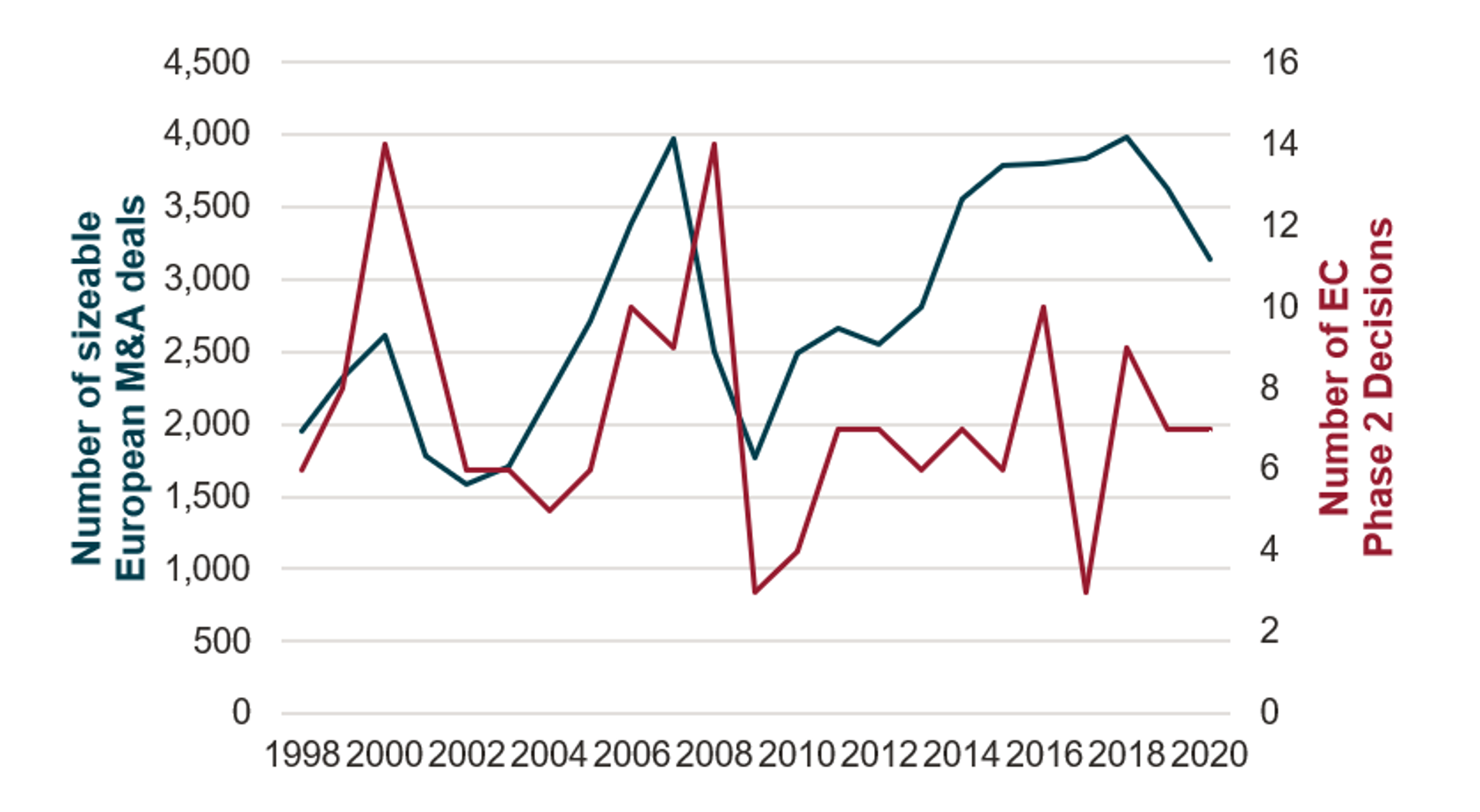

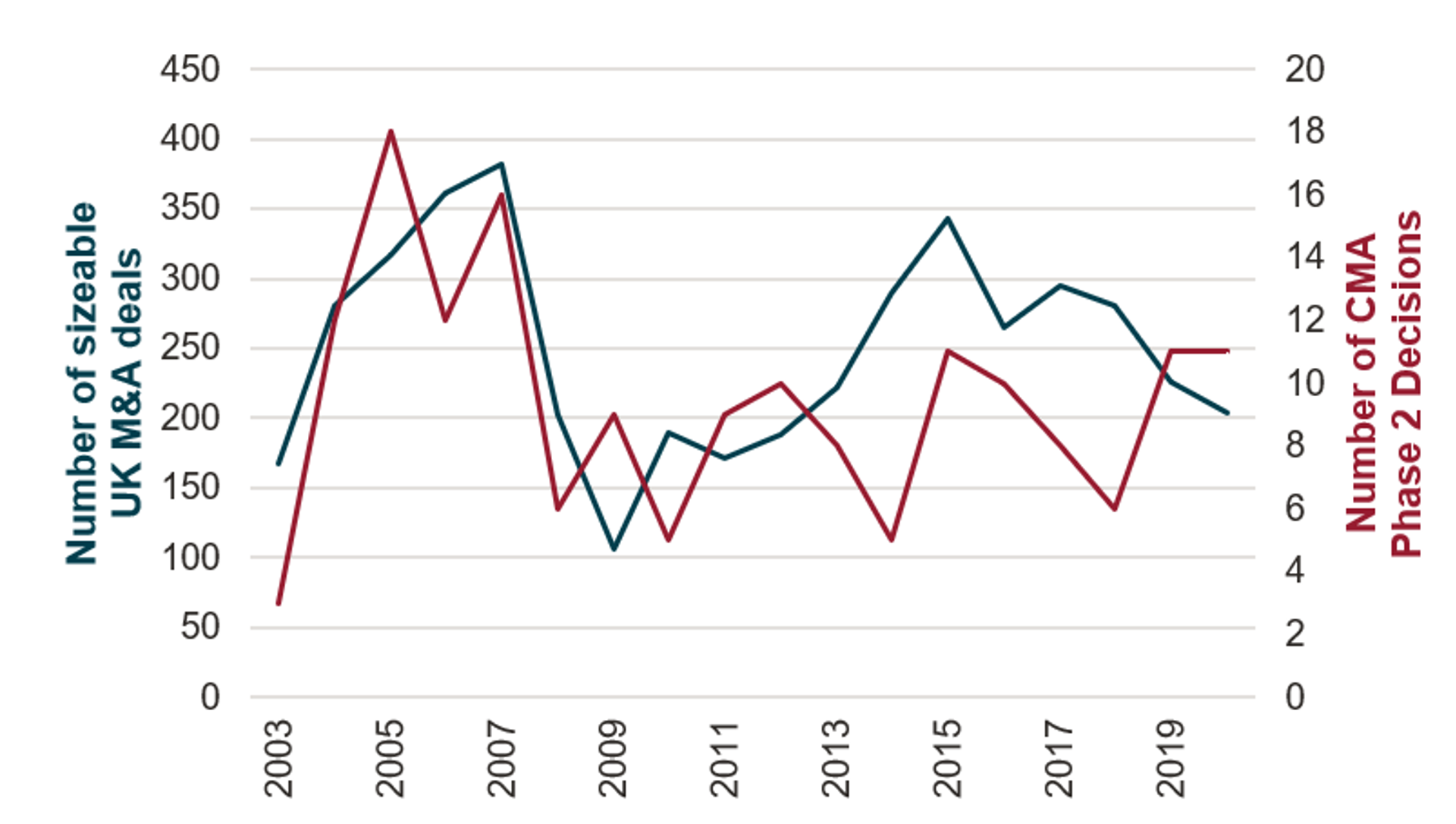

Traditionally the job of smoothing out the ups and downs of economic cycles has been left to central banks and treasury departments, leaving “microeconomic regulators” like competition authorities free to focus on other matters. Antitrust watchdogs use the same toolkit to investigate competition issues in a recession as they do when the economy is in good health, and the overall mix of work they take on usually changes comparatively little over the cycle. Take merger investigations. As the charts below show, both the European Commission (EC) and the UK’s Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) undertake a handful of in-depth merger investigations every year, and year-on-year changes in the number of cases they take on have only been loosely correlated with total levels of M&A activity since the 2008 financial crash. The number of investigations that competition authorities carry out into cartel activity and abuses of dominance similarly show no strong correlation with the economic cycle.

Figure 1 – comparison of number of in-depth EC merger investigations to levels of M&A activity in Europe

Sources: Frontier Economics analysis of EC merger investigation portal; Bloomberg.

Notes: Deal count is number of sizeable European M&A transactions where the target business had annual revenues of at least $100m.

Figure 2 – comparison of number of in-depth UK merger investigations to levels of M&A activity in the UK

Sources: Frontier Economics analysis of CMA investigation portal; Bloomberg.

Notes: Deal count is number of sizeable UK M&A transactions where the target business had annual revenues of at least $100m; the investigation count includes Phase 2 merger investigations by the UK Competition Commission before the formation of the CMA in 2013.

On one level this is unsurprising. The analytical techniques that competition authorities use to allow them to take account of the wider economic backdrop when, for example, considering the impacts that a proposed merger will have on competition. And calls to relax competition law during economic downturns are rightly met with scepticism: monopolies and cartels are bad news for consumers at all stages of the economic cycle, and allowing shotgun mergers or state aid to prop up underperforming companies in a recession could have damaging long-term consequences.

Nonetheless, at a time of intense pressure on government budgets and ominous talk of “quango bonfires”, regulators are being asked to think again about whether they are making the most effective use of their limited resources. And competition authorities may find themselves with questions to answer. For instance, with a continued drop-off in merger activity forecast for 2023, should they be filling their boots with their standard quota of merger investigations, or should they focus on other priorities?

What might a more targeted competition policy regime look like? Two issues that have been pre-occupying competition authorities for some time are whether competition policy needs to be updated to facilitate green initiatives (a topic we covered in our 2022 outlook article) and the regulation of digital markets (see next section). However, the severity of the cost-of-living crisis is prompting some to ask whether there should be a greater emphasis on markets that matter most to households that are struggling to make ends meet. A thought-provoking recent study in the UK found that that markets for essential goods that take up a larger share of the budgets of poorer households tend to be more concentrated than other markets – a point noted by the CMA in its 2022 report into the state of competition. From a societal perspective, might it be more important to concentrate on eking out modest improvements in these markets than on assessing the impact of mergers in, say, the computer games sector?

All very well, competition authorities might respond, but we have limited room for manoeuvre. And they would have a point. The EC, for example, has a duty to investigate all mergers that meet certain turnover thresholds. This means that economic sectors with high levels of M&A activity can take up much of the bandwidth of regulators in Brussels, irrespective of whether the markets concerned are essential or could greatly improve outcomes for consumers. And even where they do investigate mergers in these sectors, their freedom to act is limited, since merger control cannot be used to address wider competition problems that might beset these markets: regulators can block a deal if they think it will substantially damage competition, but they cannot take any further steps to leave the market in a better state than they found it.

However, some national competition authorities have more flexibility as to where they direct their efforts. The UK, for example, has a voluntary merger reporting regime, under which there is no hard obligation on firms to notify their transactions to the CMA. This gives the CMA more discretion as to which mergers it chooses to investigate. Moreover, the CMA – alongside a handful of other European competition authorities in Italy, Romania, Greece and Iceland – has wide-ranging investigation powers that allow it to make targeted interventions to boost competition in markets even where there have been no breaches of competition law. In practice, the CMA has made limited use of this tool in the last five years (perhaps out of wariness, after completing two heavy-going market investigations into the energy and retail banking sectors in 2016 and 2017). This year, however, could mark a new chapter for UK competition policy, with a new chair and interim chief executive having taken up their posts at the CMA in recent months. And with the UK government publicly pressurising the CMA to ensure that tax cuts designed to mitigate inflationary pressures on businesses are swiftly passed on to customers, a revival of the CMA’s market investigations regime could be on the cards.

Elsewhere in Europe moves are afoot to arm competition authorities with investigatory tools similar to those of the CMA. The EC itself got the ball rolling in 2020, with proposals for a New Competition Tool (NCT) that would allow it to intervene in markets pre-emptively to improve competition, rather than having to wait for a formal breach of competition law. These proposals met resistance, with concerns expressed that there was not a strong legal basis to give the EC these powers under the current treaties governing its operation. However, it is possible that they could resurface with the intensification of the cost-of-living crisis and calls for a more joined-up EU-wide response.

In any event, national competition authorities are now picking up the baton. In Germany concerns about a decoupling of prices charged at the petrol pump from the crude oil price in the aftermath of Russia's attack on Ukraine have led to calls for the Federal Cartel Office (FCO) to be handed investigatory powers similar to those held by the CMA. The FCO has already published an interim report into the operation of refineries in Germany and the pass-through of costs to consumers, while moves are underway to update German competition law to give the office more powers to intervene off the back of its findings. With Europe’s most powerful economy revamping its competition regime to respond to the crisis, it will be intriguing to see whether others follow.

Click here to read about Antitrust's digital revolution, the rise and rise of collective actions and Subsidy control